To Read Is to Fly

“To read is to fly: it is to soar to a point of vantage which gives a view over wide terrains of history, human variety, ideas, shared experience and the fruits of many inquiries.”

― Alberto Manguel

You can also find me on Goodreads and LibraryThing.

quarterlyconversation.com/blinding-volume-i-the-left-wing-by-mircea-cartarescu

My review of Mircea Cărtărescu's Blinding: The Left Wing is now posted on The Quarterly Conversation.

4

4

1

1

2

2

John Brown's violent battle against slavery in the US, his 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry, and his subsequent execution are well-documented in American history texts, although he remains a complicated figure, whose considerable mythology threatens to overshadow the man. Some of his sons are referenced in survey history texts because of their role in the Harper's Ferry raid. However, Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz noted that his second wife, Mary, and his daughters and daughters-in-law got little recognition from historians. In this collective biography, The Tie That Bound Us , she combs the historical record, reading letters and news accounts, and poring over photographs in the attempt to understand these women. Did they share John Brown's beliefs? How did they cope with his execution and the unwanted fame that followed? Is it possible to restore them to the historical record?

John Brown's violent battle against slavery in the US, his 1859 raid on Harper's Ferry, and his subsequent execution are well-documented in American history texts, although he remains a complicated figure, whose considerable mythology threatens to overshadow the man. Some of his sons are referenced in survey history texts because of their role in the Harper's Ferry raid. However, Bonnie Laughlin-Schultz noted that his second wife, Mary, and his daughters and daughters-in-law got little recognition from historians. In this collective biography, The Tie That Bound Us , she combs the historical record, reading letters and news accounts, and poring over photographs in the attempt to understand these women. Did they share John Brown's beliefs? How did they cope with his execution and the unwanted fame that followed? Is it possible to restore them to the historical record?Unfortunately, primary source challenges pose some serious difficulties for Laughlin-Schultz, especially as she tries to discover Mary Brown's beliefs about abolition, and about her husband's decision to turn to violence in support of abolition. She was a quiet, stoic figure, who, with only a handful of exceptions, kept her beliefs and views to herself in the letters that she wrote, both to her husband and children, and later to abolitionists who vied for her agreeing to let them use her husband's memory, and her surviving children, to further their cause. What to do with John Brown's body, how their daughters should be educated, how to disburse the funds donated to the family -- abolitionists fought each other to gain influence over Mary, and were frustrated when she did not accede to their will. Laughlin-Schulz does her due diligence, and is especially adept at describing the celebrity that attached itself to Mary Brown and her family after the Harper's Ferry executions. She tells a story that is reminiscent of contemporary media feeding frenzies. In some cases, though, she is forced to speculate about what Mary Brown must have felt, or might have believed, without having real evidence for her suppositions.

Laughlin-Schulz also faces some difficulty in understanding Browns' daughters beliefs, also due to primary source challenges. Brown's daughter Annie, who kept house for her father and his raiders, in part to try to keep neighbors from becoming suspicious, lived a complicated life. She was proud of her role in the raid, but frustrated that she never seemed to get her due from journalists, abolitionists, and politicians writing about it later. According to Laughlin-Schulz, Annie showed some signs of trauma after the raid from the pain of hearing about the execution of the raiders with whom she lived for weeks. Throughout her life, Annie lived in extreme poverty, and her later writings and comments about the raid and her beliefs are difficult sources to interpret, both because of their retrospective nature and because of her bitterness after a lifetime of being overlooked. To her credit, Laughlin-Schulz describes the uncertainties about Annie, and the pressures on her life. The portrait of her that emerges is obscured by time, but reflects some of the intense pressures she faced throughout her life as a result of her relationship with her father.

In spite of the source challenges that Laughlin-Schultz faces, The Tie That Bound Us kept my attention. Laughlin-Schultz writes with sympathy for the Brown women, and her ability to recreate the political and cultural context surrounding the Browns makes this a good book to read to learn more about the complicated atmosphere around abolition in the US in the mid to late 19th century.

3

3

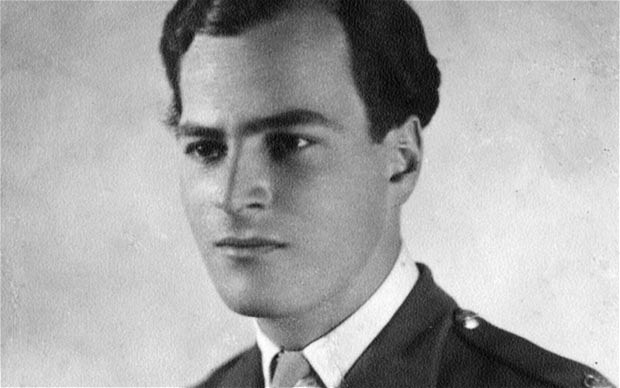

Patrick Leigh Fermor seems to have led a charmed life. He died in 2011 at the age of 96, after living an unorthodox life on his own terms. Leigh Fermor was a war hero, serving as an intelligence officer on Crete and operating throughout Greece during World War II. He now is best known as a travel writer -- indeed, his [b:A Time of Gifts|253984|A Time of Gifts|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321602492s/253984.jpg|2636997] is one of my favorite books of all time. In this affectionate biography, Artemis Cooper uses letters and interviews, publications and journal entries, to describe Leigh Fermor's life in all its complexity, conflict, and joy. This biography is likely to be of interest to readers who already love Leigh Fermor's writing, but it may also bring new readers to his work.

Patrick Leigh Fermor seems to have led a charmed life. He died in 2011 at the age of 96, after living an unorthodox life on his own terms. Leigh Fermor was a war hero, serving as an intelligence officer on Crete and operating throughout Greece during World War II. He now is best known as a travel writer -- indeed, his [b:A Time of Gifts|253984|A Time of Gifts|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321602492s/253984.jpg|2636997] is one of my favorite books of all time. In this affectionate biography, Artemis Cooper uses letters and interviews, publications and journal entries, to describe Leigh Fermor's life in all its complexity, conflict, and joy. This biography is likely to be of interest to readers who already love Leigh Fermor's writing, but it may also bring new readers to his work.

Leigh Fermor was born in 1915 in London to Lewis Leigh Fermor, a respected geologist working for the English Civil Service and stationed in India, and Æileen, a free spirit who loved theatre and socializing, but who chafed against staid expectations for behavior. Paddy-Mike lived the first years of his life separated from his parents and older sister, Vanessa as we has brought up by the Martin family in Northamptonshire, to protect him from possible attack by the Germans. By all accounts, this was an idyllic period in Leigh Fermor's life, but it ended when his mother brought him to live with her in London. He was not yet five.

Leigh Fermor's parents were profoundly incompatible, so they separated and later divorced. Leigh Fermor's youth saw him veering between two extremes: a bright boy with an impressive memory and a talent for languages and history, who was also undisciplined and unwilling (and perhaps unable) to abide by rules. He loved socializing, acted without thinking of consequences, and generally let his high spirits move him to act. As a result, he had difficulty remaining in any one school for longer than a few terms. By the time Leigh Fermor turned 18, his future was in doubt. He was in debt from living a wild social life, he had no degree and no prospects for an academic or a professional future, and his lack of discipline made a tenure in the army questionable at best. Cooper traces these aspects of Leigh Fermor's personailty not only in his youth, but throughout his life. The contrast between his meditative, scholarly inclinations and his adventuresome, exuberant spirit remained a constant.

Photo by Joan Leigh Fermor

At this point, Leigh Fermor developed his plan to walk across Europe, from Holland to Constantinople. The prospect excited him -- the chance of adventure, the promise of meeting new people, the opportunity to see places he had read about in history texts and works of literature, and the ability to make his own decisions about where to go and what to do. He got some funding to help him outfit himself for life as a wanderer, made arrangements to receive his allowance in intervals on the road, and set off on December 8, 1933. The first stage of this journey later was retold by Leigh Fermor in [b:A Time of Gifts|253984|A Time of Gifts|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321602492s/253984.jpg|2636997], while stage two is related in [b:Between the Woods and the Water|293207|Between the Woods and the Water|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1320564549s/293207.jpg|807394]. (A posthumous volume collecting Leigh Fermor's writings about the final stage of the journey is set to be published in Spring 2014.)

Cooper draws heavily on Leigh Fermor's writings to tell of his travels during this period, but she also provides some additional perspective. She cites on interviews with Leigh Fermor to indicate places where he fictionalized some events. She explores the gaps between 18-year-old Leigh-Fermor's rudimentary understanding of politics and his later recognition that these political blinders made him miss many crucial details relating to the rise of Nazism in Central Europe. She later traces the difficult publication history of these volumes, as for anything that Leigh Fermor wrote. Paddy was often plagued by writer's block, He wrote very slowly, and often was distracted when he was writing. Decades after his walk through Europe, he was overwhelmed by the success of [b:A Time of Gifts|253984|A Time of Gifts|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1321602492s/253984.jpg|2636997] and [b:Between the Woods and the Water|293207|Between the Woods and the Water|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1320564549s/293207.jpg|807394]. Cooper's biography provides insight into this aspect of Leigh Fermor's life, particularly as she quotes from correspondence between Paddy and his publisher.

Princess Balasha Cantacuzène

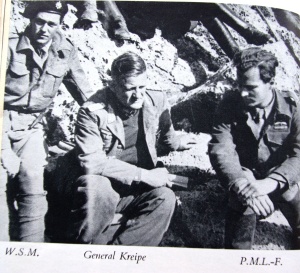

Cooper also provides insight in Leigh Fermor's life after the walk. She details his relationship with Princess Balasha Cantacuzène, a Romanian painter whom he met in Athens, and with whom he lived for years until the onset of Wrold War II. She describes his work in World War II, when he worked as a British Intelligence Officer, focusing especially on work with the Cretan Resistance Movement. His journeys through Greece and his language skills made him a valuable officer, as did his ability to forge strong relationships with people from different cultures. Leigh Fermor achieved fame for leading a successful operation to kidnap a German general on Crete. Cooper describes not only this action, but also its afterlife, including some controversy over different versions of events, and what happened when Hollywood took interest. Greece remained an important part of Leigh Fermor's life until his death. He visited often, wrote two well-received travel books ([b:Mani: Travels in the Southern Peloponnese|766421|Mani Travels in the Southern Peloponnese|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1343686627s/766421.jpg|780647] and [b:Roumeli: Travels in Northern Greece|766415|Roumeli Travels in Northern Greece|Patrick Leigh Fermor|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1343686844s/766415.jpg|752486]), and later designed and built a house there.

Moss, General Kreipe, and Leigh Fermor on Crete

For a long period of time after WWII, Leigh Fermor lived a hand-to-mouth existence. A constant in his life was Joan Rayner, whom he met just after World War II, and who was his longtime partner, and later his wife. In Cooper's portrait, Rayner emerges as a fascinating figure: calm, quiet, practical, intelligent, beloved by her close friends, and, according to Cooper, happy for Leigh Fermor to engage in affairs and spend considerable time away from her. As depicted by Cooper, theirs was not a conventional relationship. Using personal correspondence and interviews with friends. Cooper shows the depth of their mutual love and respect for each other. I would have liked more focus on Joan throughout the biography -- or, perhaps, for someone to write a biography of her. She appears as a self-contained person, someone who valued a spiritual, emotional and intellectual connection with Leigh Fermor far more than any physical relationship. She also was widely-traveled, a skilled photographer, an intelligent person with many gifts and a quiet confidence in herself.

Joan Leigh Fermor

In the end, Cooper presents Patrick Leigh Fermor as a three-dimensional figure, a man whose gifts and flaws shaped his life. He veered between depression and exhilaration throughout his life, but consistently viewed himself as profoundly fortunate. He lived outside of convention, on his own terms. Cooper does not gloss over his flaws, but explores them with sensitivity and balance. I emerged with a better understanding of his life, and a new foundation from which to approach his writings which I have not yet read.

2

2

In this slender novel, Christine Schutt has written a poem to loss and loneliness, to the anguish of losing parents, to the threat of heredity ("you're just like your mother") to the ephemeral joy of connecting, in some small way, even in fantasies; and to the saving grace of words.

In this slender novel, Christine Schutt has written a poem to loss and loneliness, to the anguish of losing parents, to the threat of heredity ("you're just like your mother") to the ephemeral joy of connecting, in some small way, even in fantasies; and to the saving grace of words.The novel is told, in short, fragmented chapters, by Alice Fivey, who opens the novel remembering a happier time, when her father was still alive and her mother was living at home:

"One winter afternoon—an entire winter—it was my father who was taking us. Father and Mother and I, we were going to Florida—who knew for how long? I listened in at the breakfast table whenever I heard talk of sunshine. I asked questions about our living there that made them smile. We all smiled a lot at the breakfast table. We ate sectioned fruit capped with bleedy maraschinos—my favorite! The squeezed juice of the grapefruit was grainy with sugar and pulpy, sweet, pink. 'Could I have more?' I asked, and my father said sure. In Florida, he said it was good health all the time. No winter coats in Florida, no boots, no chains, no salt, no plows and shovels. In the balmy state of Florida, fruit fell in the meanest yard. Sweets, nuts, saltwater taffies in seashell colors. In the Florida we were headed for the afternoon was swizzled drinks and cherries to eat, stem and all: 'Here’s to you, here’s to me, here’s to our new home!' One winter afternoon in our favorite restaurant, there was Florida in our future while I was licking at the foam on the fluted glass, biting the rind and licking sugar, waiting for what was promised: the maraschino cherry, ever-sweet every time."

Alice's father dies in an accident soon after this memory, drowning after he drove his car into a lake. Alice is only five when he dies. For two years afterwards, her mother (also named Alice) and Alice cling to the promise of a Florida where life is easy and the sun is warm, in the face of frigidly cold winters, a succession of brutal boyfriends (all of whom Alice and her mother call Walter), and an extended family that looks down on Alice Sr.'s erratic behavior. Alice's mother is loud, while her brother and mother are quiet. She is profligate in her generosity to others, while her brother and mother carefully hoard their wealth. She makes public scenes, while her brother and mother are careful to avoid unpleasant topics and keep their voices down. When Alice is seven, the family chauffeur and handyman, Arthur, drives her to The San, where she remains throughout her daughter's childhood.

Schutt is masterful in using a few words and phrases to evoke Alice's life without her mother. Living first with her wealthy Uncle Billy and Aunt Frances, and briefly in a huge mansion with her bedridden grandmother, Alice is haunted by the specter of her mother. She and her relatives continually compare her to her mother -- both are loud, "all mouth." Soon after her mother is admitted to The San, the following scene takes place: "As soon as Uncle Billy was gone, Aunt Frances caught me at the cupboards, finding my thumb in Mother’s thumb-cut crystal glasses. 'Snooping!' she said. 'Your mother liked to snoop, too. Did you know that? Next time, ask.'” Aunt Frances and Uncle Billy constantly criticize Alice's mother for being a spendthrift, suggesting that Alice may follow in her footsteps: "Aunt Frances spoke of money, of Uncle Billy’s, Nonna’s, and her own, but not my mother’s; what was left of my mother’s was knotted in trusts and Nonna was paying for me—didn’t I know that? Aunt Frances said, and said often, 'Didn’t your mother teach you?' Simple economies and healthful ways. There were rules, manners. Made beds and sailing spoons. 'Napkins first and last,' she said, 'and the napkin ring is yours,' and so it was, handwrought and hammered, a gothic napkin ring with my mother’s name, which was also mine, Alice.

"Alice, Alice, Alice, Alice!" Throughout the novel, Schutt eloquently -- and painfully -- depicts Alice's conflict between fearing she is like her mother, and hoping she is like her mother.

Schutt's writing is breathtakingly eerie, sad, beautiful, strange. With not a wasted word, she paints indelible images. The San is described as having: "Wavy grounds, old trees, floating nurses." She depicts Alice's mother just before she was driven to The San: "Mother was wearing the falling-leaves coat in the falling-leaf colors, a thing blown it was she seemed, past its season, a brittle skittering across the icy snow to where Arthur stood by the car, fogged in." Schutt lends the same deft touch to her descriptions of weather, houses, landscapes: "The air then was coppery with music...." Schutt's prose elevates this novel above its relatively simple plot.

As the book progresses, we trace Alice's life after she is living on her own in New York. As she struggles with the Walters in her own life, flies across the country to visit her mother, and seeks to become a poet, as she believes her father wanted to be, Alice must come to terms with her inheritances as well as with her individuality. There are no easy solutions to Alice's dilemmas, because they are part of life. Schutt's ability to convey the mess and uncertainty of an adult life, the tenuous ties to the past and the hesitant hopes for future, and to turn that life into poetry, is richly rewarding. This novel is highly recommended.

Many thanks to Open Road and to Netgalley for sending me this ARC.

1

1

Simone Schwarz-Bart's classic novel The Bridge of Beyond, which will be released by NYRB on August 20, 2013, is an ode to the spirit of the women of Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, caught between a colonial past and an uncertain future. In her prose, Schwarz-Bart captures the rhythm of language in Guadeloupe, as well as the longevity of folk traditions, spirits and magic, alongside a Christianity brought to the islands by French colonists. More than anything else, this magical, heart-rending, beautiful book explores the challenges faced by women living on the Caribbean island, and the spirit with which they faced challenges -- finding a way to support themselves and their children; seeking and losing love; fighting to maintain dignity in the face of white privilege and the vestiges of slavery; balancing respect for tradition with the unstoppable onset of modernity.

Simone Schwarz-Bart's classic novel The Bridge of Beyond, which will be released by NYRB on August 20, 2013, is an ode to the spirit of the women of Guadeloupe in the Lesser Antilles, caught between a colonial past and an uncertain future. In her prose, Schwarz-Bart captures the rhythm of language in Guadeloupe, as well as the longevity of folk traditions, spirits and magic, alongside a Christianity brought to the islands by French colonists. More than anything else, this magical, heart-rending, beautiful book explores the challenges faced by women living on the Caribbean island, and the spirit with which they faced challenges -- finding a way to support themselves and their children; seeking and losing love; fighting to maintain dignity in the face of white privilege and the vestiges of slavery; balancing respect for tradition with the unstoppable onset of modernity.

Sugar cane fields in Guadeloupe

Schwarz-Bart focuses her story on the lives of five generations of women in the Lougandor family, a chain of grandmothers, mothers, and daughters who fall in love, have children, suffer seemingly unbearable losses, and emerge from tragedy. Although Schwarz-Bart's narrative extends far into the Lougandor's past, the novel focuses primarily on the life of Telumee, who is raised by her grandmother Toussine after a series of family tragedies. Toussine herself is no stranger to loss. She lives alone in a hut in Fond-Zombi, in an isolated spot where she hoped her friend Ma Cia, a witch, would help her to make contact with her beloved husband Jeremiah's spirit. When Telumee leaves her family home in L'Abandonée to live with Toussine, she has a sense of excitement about the journey:

"We walked in silence, slowly, my grandmother so as to save her breath and I so as not to break the spell. Toward the middle of the day we left the little white road to its struggle against the sun, and turned off into a beaten track all red and cracked with drought. Then we came to a floating bridge over a strange river where huge locust trees grew along the banks, plunging everything into an eternal blue semidarkness. My grandmother, bending over her small charge, breathed contentment. 'Keep it up, my little poppet, we're at the Bridge of Beyond.' And taking me by one hand and holding on with the other to the rusty cable, she led me slowly across that deathtrap of disintegrating planks with the river boiling below. And suddenly we were on the other bank, Beyond: the landscape of Fond-Zombi unfolded before my eyes, a fantastic plain with bluff after bluff, field after field stretching into the distance, up to the gash in the sky that was the mountain itself, Balata Bel Bois. Little houses could be seen scattered about, either huddled together around a common yard or closed in on their own solitude, given over to themselves, to the mystery of the forest, to spirits, and to the grace of God."

Guadeloupe

The novel continues to trace Telumee's journey from childhood to adulthood. We see her playing with other children, helping Toussine with chores, and learning the rhythms of life in a community where centuries-old beliefs about spirits combined with the celebration of Christian festivals. As Telumee falls in love and moves from childhood to adulthood, her joys and her sorrows grow exponentially. Schwarz-Bart's lyrical prose depicts her passage through life with the cadences of Creole folk tales combines with lyrical, haunting descriptions of rituals, beliefs, and the beauty of the land surrounding her. Telumee doesn't divide landscape from people, the living from the dead -- in her culture, all elements and beings are interwoven, omnipresent.

Schwarz-Bart's descriptions of village life provide complex pictures of the combination of support and conflict in villages like Fond-Zombi:

"Sometimes there would be the sound of singing somewhere; a painful music would invade my breast, and a cloud seemed to come between sky and earth, covering the green of the trees, the yellow of the roads, and the black of human skins with a thin layer of gray dust. It happened mostly by the river on Sunday morning while Queen Without a Name [Toussine] was doing her washing: the women around her would start to laugh, laugh in a particular way, just with their mouths and teeth, as if they were coughing. As the linen flew the women hissed with venomous words, life turned to water and mockery, and all Fond-Zombi seemed to splash and writhe and swirl in the dirty water amid spurts of diaphanous foam."

As we follow Telumee through her life, we see finely drawn character portraits of her friends and enemies. They all bring to life the characters in this beautiful novel -- all the more beautiful because everyone is flawed, no one's life is perfect, but Telumee and her neighbors continue to strive.

Guadeloupe

I am inspired by so many aspects of this novel. Schwarz-Bart's prose captures the rhythms of stories passed from generation to generation. Seeing traditional beliefs side by side Christian ones provided a fascinating look into the complex culture of former slave communities. The visual descriptions of the landscape are striking. And, especially important to me, Telumee and Toussine emerge as three-dimensional characters who are inspirational in their ability to emerge from devastating tragedies. Highly recommended.

1

1

2

2

This is pure fun. The premise is 90% of the book, which is a satire of hard-boiled detective fiction. In this case, the detective can't drive so is constantly hitching rides from people, including a college philosophy major who delivers flowers and ends up serving as the detective's sidekick. The detective is also prone to existential rumination, painfully aware at all times of how much he doesn't, and can never, know. Staples of hard-boiled detective fiction, including the beautiful widow whom the detective falls for, the difficult relations between the detective and the police, bad guys hiding in the shadows, and the deceased's attorneys who seem to know more than they are willing to share populate the story. In the end, the mystery isn't solved, but what else could we expect, given the limitations of human knowledge? :)

This is pure fun. The premise is 90% of the book, which is a satire of hard-boiled detective fiction. In this case, the detective can't drive so is constantly hitching rides from people, including a college philosophy major who delivers flowers and ends up serving as the detective's sidekick. The detective is also prone to existential rumination, painfully aware at all times of how much he doesn't, and can never, know. Staples of hard-boiled detective fiction, including the beautiful widow whom the detective falls for, the difficult relations between the detective and the police, bad guys hiding in the shadows, and the deceased's attorneys who seem to know more than they are willing to share populate the story. In the end, the mystery isn't solved, but what else could we expect, given the limitations of human knowledge? :)

Reading Robert Walser can be a dizzying experience. The Swiss writer, who was born in 1878 in Bern and died on Christmas day, 1956 in Herisau, Switzerland, lived through a period of intense social, cultural, and political change, during which traditional ways of life in Europe began to give way to modernism, provincialism was increasingly at odds with the development of urban cultures, and respect for authority and obedience gained a sinister aspect. In a series of brilliant novels and short prose pieces, Walser leaves behind a body of work formed in the crucible of these changes. His voice is singular, his style immediately identifiable to anyone who has read even one of his works.

Reading Robert Walser can be a dizzying experience. The Swiss writer, who was born in 1878 in Bern and died on Christmas day, 1956 in Herisau, Switzerland, lived through a period of intense social, cultural, and political change, during which traditional ways of life in Europe began to give way to modernism, provincialism was increasingly at odds with the development of urban cultures, and respect for authority and obedience gained a sinister aspect. In a series of brilliant novels and short prose pieces, Walser leaves behind a body of work formed in the crucible of these changes. His voice is singular, his style immediately identifiable to anyone who has read even one of his works. Although Walser lived for decades at the end of his life in asylums, withdrawn from the world, in his earlier life he lived right at the fault lines of these changes. He served as an apprentice in a bank and later left that safe existence to live as a wandering writer. He experienced life as a successful writer in Berlin, but later left the flurry of urban life behind him, secluding himself and writing a string of novels, one of which, [b:Jakob von Gunten|513275|Jakob von Gunten|Robert Walser|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1320554619s/513275.jpg|2004083], remains the best starting point to explore his work. In 1913, Walser left Berlin to return to a quiet provincial life in Switzerland. He continued to write briefly, but he had difficulty adjusting to cultural and social changes which were accelerating after World War I. Although he continued to write sporadically, his transient lifestyle and inability to find the equilibrium to carve out a life for himself led him to be committed to a sanatorium in Waldau. He was transferred from Waldau to another asylum in Herisau in 1933, where he lived until his death. (See the wonderful review by J.M. Coetzee, "The Genius of Robert Walser" in the New York Review of Books for more details about his life and work: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2000/nov/02/the-genius-of-robert-walser/?pagination=false)

NYRB has played an instrumental role in the Walser renaissance, which continues in their upcoming release of this collection, A Schoolboy's Diary and Other Stories (release date September 3, 2013). In it, editor and translator Damion Searls brings together short prose pieces and stories that cover most of Walser's writing career. Some pieces are short sketches. Others are stories. And some are written in the form of brief essays by schoolboys. The selections are well-chosen, and provide an extraordinary perspective on some of the elements that make Walser a unique, important, and beloved writer.

Some of the elements of Walser's style and approach that I appreciate the most are visible in this collection. One of his favorite themes is that of unquestioning obedience by schoolboys and apprentices. In a pure, simple style Walser shows through sudden mood swings and contradictory assertions the irrationality of an authoritarian social and educational system. In the schoolboy essays of Fritz Kocher, Walser gives full, and often humorous, voice to a cultural system that celebrates obedience and punishment. In the essay "Poverty," Kochler writes: "Someone is poor when he comes to school in a torn jacket. Who would deny that? We have several poor boys in our class. They wear tattered clothes, their hands freeze, they have unbeautiful dirty faces and unclean behavior. The teacher treats them more roughly than us, and he is right to. Teachers know what they're doing." In the essay "Man," Kocher follows a stream of consciousness trail that leads him to ask to be punished: "Secretly, I love art. But it's not a secret anymore, not since right now, because now I've been careless and blabbed it. Let me be punished for that and made an example of." In the essay "School," Kochler abrogates all responsibility for certain topics to authority figures:

"In fact I'm surprised we were even given this topic at all. Schoolboys cannot actually talk about the value of school and need for school when they're still stuck in it themselves. Older people should write about things like that. The teacher himself, for instance, or my father, who I think is a wise man. The present time, surrounding you, singling and making noise, cannot be put down in writing in any satisfactory way. You can blabber all kinds of nonsense, but it's a real question whether the mishmash you write (I allow myself the bad manners of describing my work in this way) actually says and means anything. I like school. Anything forced on me, whose necessity has been mutely insisted upon by every side, I try to approach obligingly, and like it. School is the unavoidable choker around the neck of youth, and I confess that it is a valuable piece of jewelry indeed!"

In addition to his focus on obedience, Walser also writes beautiful prose describing country scenes, some of which seem to relate to a fairy tale past that is more and more difficult to see with the onset of modernity and urbanization. In "Ascent by Night" (1914), Walser writes: "I was taking the train through the mountains. It was twilight and the sun was so beautiful. The mountains seemed so big and so powerful to me, and they were too. Hills and valleys make a country rich and great, they win it space. The mountainous nature struck me as extravagant, with its towering rock formations and beautiful dark forests soaring upward. I saw the narrow paths snaking around the mountains, so graceful, so rich in poetry. The sky was clear and high, and men and women were walking along the paths. The houses sat so still, so lovely, on the hillsides. The whole thing seemed to me like a poem, a majestic old poem, passed down to posterity eternally new." As he continues on foot, the narrator keeps banging his head on trees in the dark forest, but he laughs at the pain.

In the story "Hans" (1919), Walser conveys the clash between the freedom of a wandering life, and the looming call of Duty in the form of military service. Hans has lived the free life of a wanderer, rambling through the countryside, in his view living just as well as a baron because he can swim, he can walk where he chooses, he has the freedom to enjoy the beauty of nature and the goodness of others. Hans' response to a military mobilization represents, in a few short paragraphs, the profound ways that world War I transformed life in Central Europe. The story is beautifully written, with a jarring ending that brings home the irreversible changes of life in Europe after WWI.

For the quality of the writing, the temporal scope of the pieces, and the themes it presents, this collection is highly recommended to fans of Robert Walser, new and old alike.

The Colonization Movement in the United States is an important stage in the history of slavery and American racism, but it often gets only a brief note in survey histories of the United States. The American Colonization Society, founded in 1816, promoted the founding of colonies in Western Africa, where freed African slaves and their descendants could live lives as free peoples, outside of the specter of slavery in the United States. This Society helped to send freed blacks to Western Africa, eventually founding Liberia in 1847.

The Colonization Movement in the United States is an important stage in the history of slavery and American racism, but it often gets only a brief note in survey histories of the United States. The American Colonization Society, founded in 1816, promoted the founding of colonies in Western Africa, where freed African slaves and their descendants could live lives as free peoples, outside of the specter of slavery in the United States. This Society helped to send freed blacks to Western Africa, eventually founding Liberia in 1847. Like so many aspects of American history, the story of the Colonization Movement is marked by deep veins of racism. Some abolitionists and clergy opposed slavery, but questioned whether freed slaves could live as productive, integrated, respected members in American society. And some proponents of slavery feared that the existence of any free African-Americans would undercut the institution of slavery, provoking much-feared slave rebellions and riots.

In By the Rivers of Water: A Nineteenth-Century Atlantic Odyssey beautifully and sensitively tells the story of the Colonization Movement, the deep divisions of racism in the US, and the complex beliefs of some white Southerners through the lives of John Leighton Wilson and his wife Jane Bayard Wilson. The Wilsons were born to slaveholding families in Georgia and South Carolina, but followed their religious beliefs to serve as Protestant missionaries in West Africa, arriving in 1834 and living and working there for 17 years, when poor health forced them to return to the United States.

Erskine Clarke writes in his introduction that his focus as a historian is not simply to record facts, but to hear and represent "individual voices" from many different cultures: Gullah slaves and members of Grebo and Mpongwe tribes; Presbyterian missionaries and colonial authorities; white slaveowners and abolitionists; and former friends from the North and the South divided by the anguished divisions of the US Civil War. And he succeeds brilliantly. Clarke utilizes anthropological and archaeological sources and perspectives, as well as delving into more traditional historical documents, especially letters written by John Leighton Wilson. He writes with sensitivity of the clash of religious and cultural beliefs as well-meaning missionaries confront and attempt to form relationships with members of different African tribes. He traces the conflicts among the settlers of these colonies, the missionaries, and the Grebo and Mpongwe peoples. And he tells about the Wilsons' experiences as they built up missions in Cape Palmas among the Grebo, and on the Gabon estuary among the Mpongwe.

Perhaps most impressive is Clarke's treatment of John Leighton Wilson, who emerges from this biography as a man whose beliefs represent some crucial conflicts of his time. He was opposed to slavery and took actions to free his slaves and his wife's slaves, but he supported the Confederacy during the Civil War. He supported freedom for slaves, but his characterizations of the African-American settlers and administrators of the colonies closest to his missions reveal his belief that blacks were, in the end, inferior to whites. Wilson undertook studies of various West African languages and took steps to understand Grebo and Mpongwe beliefs and the complexity of changing those beliefs, a more nuanced understanding than many Americans had at this time, but one in which he still privileged a specific Christian belief and culture as the only path for salvation and civilization for any person. Understanding Wilson helps us to understand how deeply racism was ingrained in 19th-century Americans. Clarke follows the Wilsons through their return to the US, through the American Civil War, and into Reconstruction. Their responses to these cataclysmic events and changes provide needed context for any understanding of the complex views on slavery held by some American Southerners.

Clarke's research is extensive, his writing is clear and, at times, beautiful, and his sensitivity to nuance is laudable. I highly recommend this book, which will be published by Basic Books on October 8, 2013, to readers with interests in biography, religious history, the history of American slavery and racism, and the US Civil War.

I definitely am not the right audience for this book. I struggle with sweeping historical surveys at the best of times. I always want more context, more quotations from primary sources, more in-depth analysis than is realistic for a sweeping survey covering thousands of years of history in 700 pages. So you should take my reactions to this book with a grain of salt.

I definitely am not the right audience for this book. I struggle with sweeping historical surveys at the best of times. I always want more context, more quotations from primary sources, more in-depth analysis than is realistic for a sweeping survey covering thousands of years of history in 700 pages. So you should take my reactions to this book with a grain of salt. There are many aspects of Herman's book that are laudable. He has extensive endnotes to show that he has done thorough research in the history of Western philosophy. I tend to balk at premises such as his -- the conflict between Plato's championing of the ideal and Aristotle's focus on experience formed the foundation for much of Western thought through the 20th century -- but it is true that both Greek philosophers' influences have loomed large. Herman is also writing for a general audience, not for an audience of academics, and there's a good chance that his style and approach will attract many general readers, and in turn may lead them to more in-depth forays into Western philosophy.

In the end, though, in spite of these strengths, I was disappointed by this book. Herman does spend some time presenting limited historical context for the philosophers that he studies, but the context is quite limited and pales compared to the Plato versus Aristotle paradigm. This is likely my training as a social historian skewing my response, but I worry about reductive paradigms, and in the end the Plato versus Aristotle paradigm seems quite reductive to me unless it's balanced by an equal attention to how philosophers from past societies combined and transformed other influences as well. Again, Herman does this to some extent, but I would have liked to see much more of this.

Herman also tapped into some of my pet peeves in writing. He tends to end each chapter with a strong pronouncement along the lines of "Soon would come Philosopher X to {make some sweeping transformation in Western thought}." I know this is a typical approach to writing surveys -- have a juicy hook at the end of each chapter to prepare for the next one -- but I prefer more understatement. Also, Herman regularly presents physical descriptions of philosophers who are always running through their towns or pacing through studies and then beginning to write. Again, I know this is supposed to provide color and interest for general readers, to make them feel like they are in the presence of the philosophers, but since the descriptions don't go beyond appearances, I don't think they add much.

Readers who are quite familiar with Western philosophy are not the target audience for this book. They will likely be frustrated by the quick coverage of philosophers' writings and theories. I do think this is a book to which generalists and newcomers to philosophy will gravitate and enjoy. I hope that it leads them into more detailed studies in philosophy.

It would be easy to assume that Interstate comes across as a kind of MFA writing exercise: in eight different sections, tell and retell the horrific story of a shooting on an interstate, in which a father and his older daughter watch his younger daughter die. But this is not some postmodern version of the film Groundhog Day, nor does it come across as a novel built more on style and flash than substance and heart. Dixon has serious themes he is exploring, and the novel's structure is in service to those themes.

It would be easy to assume that Interstate comes across as a kind of MFA writing exercise: in eight different sections, tell and retell the horrific story of a shooting on an interstate, in which a father and his older daughter watch his younger daughter die. But this is not some postmodern version of the film Groundhog Day, nor does it come across as a novel built more on style and flash than substance and heart. Dixon has serious themes he is exploring, and the novel's structure is in service to those themes. At the heart of the novel is Dixon's blistering exploration of violence in American society. The most obvious example is the anguish that Nathan Frey feels over the inexplicable death of his young daughter Julie, and the repercussions of this death for Nathan, his wife, and his daughter Margo. I can see why some readers couldn't finish this novel. I found the opening two sections to be so wrenching, so visceral, that I had to pace myself, and read short sections in brief sittings. I have read books with disturbing subject matter before, but Dixon's novel affected me even more than usual. Dixon's writing style, with many long, run-on sentences, brings the reader directly into Nathan's memories, into his tortured recollections of this terrible event. The result is an almost claustrophobic connection with Nathan, but also an inspired reconstruction of how we talk to ourselves and, most important, how we relive and recreate memories of traumas. Dixon's exploration of the instability of memory is fascinating. Which of the retellings of these events on the interstate is true? Can we ever fix one version of reality firmly? What roles do fantasy and magical thinking have in how we experience past traumas?

In addition to the the shooting on the interstate, Dixon expands his study of violence in American culture to consider other kinds of violence, including road rage, revenge killings, generational shifts in violence and the socio-economic causes of those changes, the violence of American culture as seen in video games, and even an exasperated parent's feelings of impatience and the small but indelible acts of violence with children that those feelings generate. He explores these different manifestations throughout the different versions of the shooting, sometimes in graphic descriptions of Nathan's actions, sometimes through conversations he has with Margo and Julie (conversations that he often pitches way above their ability to understand), and sometimes through Nathan's pained recollections of his impatience with his daughters.

I struggled with this book, but I am very grateful that I read it. There are many novels that explore violence in America, but few that stayed with me for weeks, that made me think about the effects of violence in such a visceral way, that take on all the different acts of violence, big and small, that come together to create a culture of violence in the US. This is not an easy book to read, but it's a crucial book, especially to read on the heels of tragedies like the Sandy Hook shootings, and the killing of Trayvon Martin. It reminds us of the devastating personal toll of violence, and of the myriad acts of violence, large and small, that surround us -- and that we sometimes enact ourselves -- every day.

The review below is published in 3:AM Magazine: http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/origin-myths-and-incongruous-realities/

The review below is published in 3:AM Magazine: http://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/origin-myths-and-incongruous-realities/ In the opening pages of César Aira’s The Hare, Juan Manuel de Rosas, known as The Restorer of the Laws when he ruled the Argentinean confederation in the 19th century, poses the question: “is it possible to penetrate someone else’s incongruity? One’s own or anyone else’s, it made no difference, as he saw it. Even the most outrageous fantasy created at both its extremes, that of excess and of lack, the incongruity on which daily life was based.”

Aira has written an extensive oeuvre, over 70 published books and counting, based on his own forays into the incongruities of daily life. Weaving together myriad influences, from great works of Latin American literature to B-movie monsters, from canonical works of philosophy, history, and science to dime store novels, Aira creates realities in which the fantastic and the mundane are linked. In an Aira novel, you can expect plots to wander and veer off course, because the resulting diversions are more engaging and relevant to Aira than any typical conclusion could ever be.

The Hare, which is the latest English translation of Aira’s fiction released by New Directions, is in some ways not the typical Aira novel. It is twice the length of many of his other novels. As a result, the pacing is not as fast, and the novel sometimes reads as tedious, Aira’s prose as strained. It also has an ending that ties up so many loose threads in such a short time that it is reminiscent of final scenes in B-movie mysteries. In spite of these flaws, The Hare rewards careful reading, both for the insights it provides into Aira’s sense of Argentina’s past, and for Aira’s interest in the power of stories and the continuum of human experiences.

The Hare’s protagonist is Clarke, an English naturalist and brother-in-law of Charles Darwin. Clarke has travelled to the Argentine pampas in search of the legendary Legibrerian Hare, which is rumored to fly as well as hop. He is accompanied by Gauna, a gaucho of few words who acts as his scout, and Carlos Alzaga Prior, a young, romantic artist, as well as by Repetido, a horse of almost supernatural abilities. It soon emerges that each member of this small group (yes, even the horse) has his own personal reasons for travelling into the interior, despite some concerns over hostile Indians and unforgiving terrain. Each is on a personal quest, each is, in a way, searching for his own origin myth.

This small band first travels to Salinas Grande, the pastoral home of the chieftain Cafulcurá and his tribe of Huilliches. In a smoke-filled tent, Clarke listens as Cafulcurá introduces him to Huilliche metaphysics:

“I myself have sought to convey similar ideas [as Darwin], but — and look what a strange case of transformation this is — I always did it by means of poetry. In matters like these, it’s important to win people’s belief. But in this particular case, it so happens that we Mapuche have no need to believe in anything, because we’ve always known that changes of this kind occur. It is sufficient for a breeze to blow a thousand leagues away for one species to be transformed into another. You may ask me how. . . . it’s simply a matter of seeing everything that is visible, without exception. And then if, as is obvious, everything is connected to everything else, how could the homogeneous and the heterogeneous not also be linked?”

This theme of continuity runs throughout The Hare . Aira explores it through the myths and philosophies of the Indians whom Clarke meets on his travels. It also emerges through Clarke’s own speculations based on his observations of the physical world:

“Clarke wondered if he was at the far end of the Indians’ bathing area. As he thought about it, he became curious to see what lay beyond. Considered as a line of water that dissected the plain, the stream was a homogeneous whole, whose attractions were interchangeable, but moving along it, it changed without changing, in direct proportion to the distance traveled.

“Clarke stood up and, just as he was, without shoes or trousers, walked on about a hundred yards. A different aspect of the stream and its banks presented itself to him, novel despite being vaguely predictable. It was a kind of reworking of the same elements: water, the riverbanks, trees, grass. Fascinated, he walked on further, in the midst of complete silence. All the charm of the place lay in its linear aspect, the way each of its segments was hidden from the previous one: the very opposite of what happened out on the open plain. As he had thought, there was no one around. Even the distant sounds of voices and noises he had heard from time to time on the little beach no longer reached him. The river was a series of secret chambers, following on from each other as in an Italian palace. As he crossed a number of “thresholds,” the mechanism of increasing distance led Clarke to feel he was entering a world of mystery, a self-contained nothingness that invoked the infinite.”

In this world, surprises and mysteries await along a continuum. Aira has envisioned interconnected worlds, almost like panels in a comic strip. They are connected, a person can travel from one to the other, and they allow for swings between the imaginary and mythic, and the physical and rational. Aira uses this construct to explore Argentina’s past, split between the mythic world of the Indians and the rational world of the white settlers. He conceives of the pampas as a blank canvas, described by Cafulcurá’s son Alvarito Reymacurá as a place of discontinuities, which the Mapuche Indians filled with continuities that they created themselves through the stories they told.

Clarke soon discovers from the shaman Mallén that Cafulcurá governs the Huilliche through stories and myths. Indeed, Cafulcurá’s power stems from his own origin myth, fantastic events that led to his being rescued after being kidnapped during his 35th birthday celebrations.

“Bear in mind that this incoherent old man, high on grass, who gave you all the rigmarole about the continuum, has for the past fifty years borne on his shoulders all the responsibility of governing an empire made up of a million souls scattered throughout the south of the continent, and has done, and will continue to do, a pretty good job. From his youth onward, Cafulcurá has worshipped simplicity and spontaneity. But one can’t help thinking, and as soon as one does, all simplicity goes to the devil….

“Which explains,” Mallén went on, “his consumption of hallucinogenic grasses, although I must admit it’s gone a bit far of late. He uses them to create images, which interact with words to create hieroglyphs, and consequently new meanings. Given the prismatic nature of our language, there is no better way of bringing out meaning, in other words, of governing. And also, given that his own personal standing is based on his position as a man-myth, how could he think in any other fashion? He’s looking for speed, speed at any cost, and so he turns to the imaginary, which is pure speed, oscillating acceleration, as against the fixed rhythm of language.”

When Cafulcurá suddenly disappears, a victim of an apparent kidnapping foretold by Huilliche myth, Clarke and his companions agree to travel in search of him. Clarke encounters two other groups of Indians who pose a stark contrast with the Huilliche: the European-influenced Vorogas, ruled by the chieftain Coliqueo, and a group of Indians living underground, ruled by the chieftain Pillán. In these passages, Aira echoes medieval and early modern European travel literature, where exotic peoples served as symbols for certain values. Each settlement represents a different way to live: the orderly lives of the Huilliche are supported by stories and myths; the Vorogas’ chaotic lives, driven by sex and greed, show the influence of the white settlers with whom they sometimes lived; and the underground tribe of Vorogas replace a violent life with one of indolence. In one scene, Clarke compares Coliqueo’s Vorogas with the Huilliches of Salinas Grande:

“The Vorogas looked exactly the same as the Huilliches, except that they spoke a different language; once out of earshot, this distinguishing feature naturally disappeared. And yet it was still there. Since in reality nothing is imperceptible, thought Clarke, the difference was absolute, and involved their entire appearance. And the difference could be summed up by saying that in Salinas Grandes the Indians lived outside life, whereas here they were inside it. He had landed directly in the realm of fable, which he had taken to be real; now he had to get used to the idea that this fable was merely an island in the ocean of normal life. Plebeian and westernized, the Vorogas were a reminder of the ordinary things in society. To be completely ordinary, all that was needed was for them to work. Of course, there was no danger of them making that sacrifice, not even for aesthetic reasons.”

Clarke’s speculations about the differences among the tribes resonate with 19th-century European preoccupations with classifying people as well as flora and fauna. However, where the Indians fall on the continuum of civilized to savage is different than many of Clarke’s peers might expect. Coliqueo’s Vorogas are the most corrupt because of their contact with white settlers. Myths and stories and superstitions form a stable basis for the lives of the Huilliches, who live in a clean, quiet, pastoral setting. In the end, Clarke learns the importance of cultural relativism, an anachronistic touch in a book set in the 19th century:

“He had to admit [Gauna’s tale] was a very solid and plausible story, but that was entirely due to the fact that it included all (or nearly all) the details of what had happened in reality; by the same token, there must be other stories which did the same, even though they were completely different. Everything that happened, isolated and observed by an interpretative judgment, or even simply by the imagination, became an element that could then be combined with any number of others. Personal invention was responsible for creating the overall structure, for seeing to it that these elements formed unities. Of course, Clarke was not going to put himself to so much trouble . . . but he could swear, a priori, that apart from Gauna’s version, there must be an endless number of other possible stories. Moreover, between one story and another, even one that was really told and another that remained virtual, hidden and unborn in an indolent fantasy, there was not a gap but a continuum. And the existence of such a continuum, which at that moment appeared to Clarke as an undeniable truth, created a natural multiplicity, of which Gauna’s story was shown to be merely one more example. But Clarke had no intention of telling Gauna this, because that would be to run the risk of no longer counting on his company. To Gauna, his story was not simply one among many, but the only one.”

Throughout his journeys, Clarke learns to value the power of origin myths – ones explaining the beginnings of an individual, a tribe, a nation, or, in the case of Darwin, a species. Aira incorporates elements from all these examples of origin myths, as well as from captivity narratives, family histories, and other stories told around campfires, read in published volumes, watched on a movie screen. The Hare is not a tightly constructed novel. Aira’s influences from myths and history swirl around the narrative, occasionally bumping into a scene from a Hollywood Western or a surreal hallucination. Aira, true to form, follows his diversions gleefully. However sloppy and – at times – tedious The Hare is, it is worth reading for Aira’s idiosyncratic explorations into the continuum of human existence.

This is a fantastic collection of short stories. Matt Bell shows a great deal of range in styles and settings -- from the OuLiPo influenced "An Index of How Our Family Was Killed," to the extended and subdued horror of "The Receiving Tower," from the fantastically rearranged story of Red Riding Hood in "Wolf Parts," to the nightmarish story of the Collyer brothers, historical hoarders extraordinaire, in "The Collectors." As a writer of short fiction, Matt Bell contains multitudes. The range of the worlds he creates in this collection, and the consistently high level at which he is writing throughout, are impressive. I raced through the collection, and am planning to re-read it soon. Recommended to adventurous readers willing to go wherever Bell takes them.

This is a fantastic collection of short stories. Matt Bell shows a great deal of range in styles and settings -- from the OuLiPo influenced "An Index of How Our Family Was Killed," to the extended and subdued horror of "The Receiving Tower," from the fantastically rearranged story of Red Riding Hood in "Wolf Parts," to the nightmarish story of the Collyer brothers, historical hoarders extraordinaire, in "The Collectors." As a writer of short fiction, Matt Bell contains multitudes. The range of the worlds he creates in this collection, and the consistently high level at which he is writing throughout, are impressive. I raced through the collection, and am planning to re-read it soon. Recommended to adventurous readers willing to go wherever Bell takes them.

I have heard very good reports on Shambhala's "The Best Buddhist Writing" series, so I was excited to have the chance to read an ARC of the 2013 edition via Netgalley. I found this volume to have a wide-ranging collection of essays and excerpts from books covering everything from introductions to meditation and to basic concepts in Buddhism, to engaging slice-of-life essays exploring how the writers incorporate mindfulness in hectic lives, and even a piece in which Kay Larson traces the influences of Buddhism on John Cage's 4'33" (drawing on her work in her book [b:Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists|16171197|Where the Heart Beats John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists|Kay Larson|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1372041993s/16171197.jpg|21763103]. The Table of Contents presents a who's who of Buddhist writers, both established writers and relative newcomers: Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, Joseph Goldstein, Natalie Goldberg, Sylvia Boorstein, Dzongsar Khyentse, Sakyong Mipham, Norman Fischer, Philip Moffitt, Karen Miller, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, Kay Larson, and Lodro Rinzler. This volume is a wonderful introduction to recent writings on Buddhism and mindfulness, and should help readers to find new favorite writers in the field.

I have heard very good reports on Shambhala's "The Best Buddhist Writing" series, so I was excited to have the chance to read an ARC of the 2013 edition via Netgalley. I found this volume to have a wide-ranging collection of essays and excerpts from books covering everything from introductions to meditation and to basic concepts in Buddhism, to engaging slice-of-life essays exploring how the writers incorporate mindfulness in hectic lives, and even a piece in which Kay Larson traces the influences of Buddhism on John Cage's 4'33" (drawing on her work in her book [b:Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists|16171197|Where the Heart Beats John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists|Kay Larson|http://d202m5krfqbpi5.cloudfront.net/books/1372041993s/16171197.jpg|21763103]. The Table of Contents presents a who's who of Buddhist writers, both established writers and relative newcomers: Pema Chödrön, Thich Nhat Hanh, Joseph Goldstein, Natalie Goldberg, Sylvia Boorstein, Dzongsar Khyentse, Sakyong Mipham, Norman Fischer, Philip Moffitt, Karen Miller, Tsoknyi Rinpoche, Kay Larson, and Lodro Rinzler. This volume is a wonderful introduction to recent writings on Buddhism and mindfulness, and should help readers to find new favorite writers in the field.

Update on September 12, 2013: I just received the hardcover, and the photographs are amazing. Upped my star rating to 5, between the photographs and some other adjustments in the text. Book is now released!

Update on September 12, 2013: I just received the hardcover, and the photographs are amazing. Upped my star rating to 5, between the photographs and some other adjustments in the text. Book is now released! ----------------------------------------

Huguette Clark was born to nearly unimaginable wealth and privilege. Her father, William A. Clark, was a copper baron who made several fortunes, particularly in mining and railroads, booming industries during America's Gilded Age. At the time of his death in 1925, he had a huge fortune to leave to his heirs, including his youngest child, Huguette Marcelle Clark.

Huguette married once, but got divorced after approximately a year. She then turned to a very private life, far from the social whirl of New York's elite. Over time, fewer and fewer people heard from her, and hardly anyone saw her. She lived in a grand apartment on New York's Fifth Ave., with her mother, an extremely valuable art collection, as well as her beloved collection of dolls, miniature houses, and Stradivarius violins. She owned extensive properties, including a mansion with an estate in New Canaan, CT that she never lived in or furnished, and a grand mansion and grounds in Santa Barbara, CA. Bellosguardo's staff were ordered to keep the estate as close to its original condition as possible, although Huguette hadn't visited in decades.

These extensive properties caught the attention of Bill Dedman, a Pulitzer-prize winning investigative journalist. When looking for his own house, he played a game many of us have -- he started to look at properties that were hopelessly out of his price range. This led him to Huguette Clark, and her empty mansions, and a mystery-- was she still alive? What was her life like? Why were these estates left empty?

In this enthralling book, Bill Dedman provides us with the answers he discovered when on his quest to learn about the reclusive Huguette Clark. He joins with one of Clark's relatives, Paul Clark Newell, Jr., who had a series of phone conversations with Huguette over a 9-year period, beginning in 1995. Newell's personal stories about his conversations with Huguette help a flesh-and-blood person to emerge from the mystery, while Dedman's training as an investigative journalist stands him in good stead, as he slowly unravels the history of W.A. Clark, Huguette Clark, and the battle over the fortune she left behind when she died on the morning of May 24, 2011, at the age of 104.

Huguette Clark (right) c. 1917 (age approximately 11) with her sister Andrée (left) and her father William A. Clark (center)

The first part of Empty Mansions presents William A. Clark's life combined with a history of the United States, particularly from the end of the Civil War through the mid-1920s. Dedman strikes a balance between biography and history, providing details of Clark's successful career as an entrepreneur (and more scandalous career in politics), while also provided context regarding the economic history of the time. I must admit to my eyes glazing over when I read some passages about the Clarks' incredible wealth, particularly descriptions of a New York mansion (since demolished) that took decadence to a new level. Still, there are human elements to balance out these lists of possessions and furnishings, particularly regarding the sad fate of Huguette's older sister, Andrée.

Dedman and Newell have a wealth of source material concerning W. A. Clark, but after Huguette's divorce, she practically falls out of the historical record. She kept more and more to herself, enjoying her mother's company, occupying herself for a time with her painting, and for longer with her collection of dolls and her research into Japanese culture. She had enough wealth to keep the world away, if that was what she wanted, so she turned her New York apartments into fortresses, and collected around her a very small group of people whom she trusted. Her reclusiveness increased even more after her mother's death in 1963.

As Dedman and Newell delve into Huguette's more recent history, they consider some disturbing questions. Were her legal and financial advisors taking advantage of her? What kind of mental health was she in? Were her reclusiveness and obsession with dolls simply aspects of her eccentricity, or symptoms of mental illness? Was she responsible to make her own financial decisions? When they discovered she had been living in a NY hospital for 20 years, they wondered why she had never been discharged. Were the medical staff and her personal nurse using their influence with her to get rich from her gifts to them? The final chapters of the book consider a battle that broke out between the beneficiaries of her will and her family members. What, in a case like this, is the appropriate way to safeguard Huguette's fortune and protect her legacy?

I found Empty Mansions to be an enthralling read -- disturbing in sections, very sad in others, but always intriguing and thought-provoking. I especially appreciated Dedman and Newell's commitment to be respectful of Huguette. A book that could have felt sensationalist instead was thought-provoking and humane. I read Empty Mansions as an ARC from Netgalley, and I liked it so much that I pre-ordered it when it comes out on September 10, 2013 from Ballantine. I know I will want to revisit Huguette's story.

1

1

1

1

Currently reading

The Upstairs Wife: An Intimate History of Pakistan

About Women: Conversations Between a Writer and a Painter

The Relic Master: A Novel

Limonov

Tourists with Typewriters: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Travel Writing

Inventing Exoticism: Geography, Globalism, and Europe's Early Modern World (Material Texts)

Among the Ruins: Syria Past and Present

Midnight at the Pera Palace: The Birth of Modern Istanbul

In Light of Another's Word: European Ethnography in the Middle Ages

Intimate Outsiders: The Harem in Ottoman and Orientalist Art and Travel Literature